Preamble

At the Shape To Fabrication “fire side chat” hosted by the infectiously chipper and energetic Arthur Mamou-Mani I admitted in public to holding an unpopular mathematical opinion. This was probably a mistake. I am after all not qualified to hold opinions—be they mainstream or unpopular—in this field. In my defence; it is not an historically unpopular opinion. At one time in the not too distant past, the Real numbers were widely scorned and ridiculed, but this state of affairs did not last long. In fact the adoption of the Reals was a much quicker affair than the adoption of most Big New Ideas™, which typically require the deaths or retirements of the old guard and the coming into power of the new. The Reals however found converts amongst the already established and famous. So who am I to side with outcasts like Kronecker, and against the giants of 19th and 20th century mathematics?

Why the Reals?

Allow me to first present to the best of my ability the case for the Real numbers. You can find all of these arguments and proofs in a myriad of textbooks, blog posts, and online videos. The internet is positively awash with the stuff, presumably because the Real numbers—like Quantum Mechanics—imply some pretty weird things which make for good click bait; scales of infinities, Cantor’s Paradox, Hilbert’s Infinite Hotel, Banach-Tarski balls, …. if you’ve spend any time at all in the YouTube maths corner you will have come across at least two of these. At any rate, here’s the abbreviated history of The Reals according to me:

- Pythagoras and his Mathēmatikoi preached the supremacy of the whole numbers and their ratios. In modern terms; everything in this world can be described by either integers or integer fractions. When it turned out this was not the case, they were not best pleased about it and in fact seem to have gone to considerable lengths to keep these counter proofs secret.

- Other Greek philosophers, most notably Eudoxus and Archimedes, less hampered by ideological considerations, made some inroads into the world beyond the rationals. Archimedes actually inventing an early form of infinitesimal calculus as part of his successful attempts to measure areas associated with chord limited parabolas. Absolutely amazing stuff, if you don’t agree with me that Archimedes was probably the smartest human to ever live, we can’t be friends.

- Not much happens for a while, certainly not in Europe. Lovely advances in mathematics elsewhere to do with polynomials, zeroes, negative numbers, and complex numbers happen, and eventually we reach the time of Euler and Gauss which we can think of as the end of ‘classical’ mathematics, before Cantor’s radical ideas usher in the ‘quantum’ era of the Real arithmetic. I’ll stop flogging that Real Number-Quantum Physics analogy now.

- The invention of the Real numbers suddenly provides mathematicians a toolkit to tackle a large range of old problems which have not seen much progress of late, and they are understandably excited by it. A few grumpy professors in tenured positions object to the wholesale adoption of these newfangled Reals and Infinite Set Theory as the new Foundations of Mathematics, but their feeble protestations wither and die in the face of this vast and unexplored mathscape.

- It is poor manners to introduce a new number system without providing a construction for its elements, and soon several competing ones are proposed, which mathematicians assure us—and I have no reason to doubt them—are all equivalent. This is good. It would be a very bad sign if there was disagreement on how to make Real numbers or what emergent properties they might have. For the remainder of this post I shall limit myself to the Axiomatic, the Dedekind Cut and the Cauchy Sequence Equivalence Class constructions, as those are the ones most commonly taught.

- Some properties of Real numbers cause mathematicians to reconsider their attitude towards the concept of infinity, or, as they soon discovered, infinities. Throughout history the very smartest mathematicians have always warned others to stay well away from thinking too much about infinity as that way madness lies. Georg Cantor however was unimpressed, and thought about these topics at length anyway, and eventually came away with some very novel ideas. Amongst these was that there exist different kinds of infinities, and that the cardinality of the set of all the Real numbers is a bigger infinity than that of the Rational numbers. This is a very important point; there are more Real numbers than there are Integers or Rationals. This makes it effectively impossible to construct real numbers from a finite amount of rationals, which is why the constructions we’re about to discuss are so … odd.

The arc of this story is not in any way unusual in mathematics or other scientific fields. New ideas encounter pushback (as they should), are critically examined for flaws (as they should) and if they withstand these trials and provide additional benefits, are adopted by the wider community as part of the language or toolkit of that field (again, as they should). The invention and adoption of the Reals in particular has clearly been a resounding success, as it has allowed mathematicians to finally nail down what calculus is actually doing and why it is rigorous after all. This had in fact been an unsolved problem of some considerable embarrassment, given the absolutely central role calculus plays. When it comes to the foundations of theoretical mathematics, it’s really best to be absolutely sure about things.

But there are some things that don’t feel quite right about all this. The initial use of Set Theory suffered a blow when Russell found paradoxes within it, and the modified Zermelo-Fraenkel Set Theories which supposedly rectify these issues are nowhere near as parsimonious, for lack of a better word. One would not expect something as ham-fisted as ZFC to lie at the bottom of all maths. I have further misgivings about the somewhat cyclical nature of the arguments for Cantor’s aleph arithmetic and the existence of uncountable sets; it very much seems to me that objects like Real numbers are required in order to prove infinities come in different flavours, and a solid theory of infinities is required to construct Real numbers.

Constructions of N, Z & Q

So let us discuss these constructions and why I do not like them. Just in case you’re fuzzy on what a construction actually is, it may make sense to briefly step back and talk about the well-behaved number systems of the Naturals, Integers and Rationals.

Before the Reals became the go-to numbers on which everything else is predicated, in fact before mathematicians considered that numbers come in systems1 at all, maths was being done using what we now call the Natural numbers. That is, the positive integers 1, 2, 3, 4, … and so on without bound2. But what is 2? What does it mean for 3 to be bigger than 2? How can we be sure that there is no other whole number bigger than 2 but smaller than 3?

To do any maths whatsoever, we must begin by making some assumptions. Ideally this list of assumptions is as short and succinct as possible. For example, one assumption on which all maths is predicated, is that we live in a logical universe devoid of actual paradoxes. It must be possible to make true statements, to differentiate between true and false statements, and for true statements today to still be true tomorrow. These initial assumptions are called axioms. To create a construction of the Naturals, we could adopt the Peano Axioms, which roughly assert that:

- The number 1 exists and is a Natural number.

- We can always add 1 to any existing Natural number to get the next Natural number.

From this we can surmise that 1 is the smallest Natural number (as there is no mechanism for creating predecessors, only successors), that 2 and 3 are indeed neighbours, and that there is no largest Natural number. Also from these axioms it is possible to define arithmetical operations such as addition, multiplication, exponentiation, tetration, equality, inequality, smaller-than and so on, along with their characteristics such as the commutativity and associativity of addition and multiplication. Pretty good progress for a small set of eminently reasonable assumptions.

But the Naturals are not good enough. We can’t reliably subtract or divide Natural numbers and end up with other Natural numbers. Subtraction is important, financial bookkeeping would be in trouble without it. So in order to fix this problem we invent an extension, which is a number system which does have a well-behaved subtraction operator. Let’s call it the Integers. We want these new numbers to be able to represent zero and negative values, which means they ought to look like this: …, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, … . However, we don’t want to start from scratch all over again. Importing a whole new set of axioms seems wasteful, so instead let’s create a construction build upon the one we already have.

We can construct an Integer to be an ordered pair [A,B] of Naturals, with the implicit meaning that the value represented by such a pair equals A-B. It has to be implicit because subtraction is not, yet, well defined. I find there is a certain twisted satisfaction in constructing a number extension using exactly the problem (subtraction) we’re trying to solve. In this construction, the Integer value six can be written as [7,1] while negative twelve can be written as [1,13]3. The benefit of this approach is that we do not have to invent any new mathematics, as all the existing operators which are already defined for Naturals can be repurposed to operate on these pairs of numbers. We can define Integer addition purely in terms of Natural addition4. For example, x+y=z where x, y, and z are all Integers is actually just this: [a,b]+[c,d]=[a+c,b+d] where a, b, c, and d are all Naturals.

This same story very much repeats when it comes to division. The division operator is not well-defined on the Integers, as one-divided-by-five cannot be represented by an Integer value, but we can define an extension called the Rationals, and we can construct a Rational number to be an ordered pair [X,Y] of Integers. More commonly we denote this pair using fraction notation instead: ⅕.

Constructions of R

No such sleight of hand is going to work for the Real numbers. As previously mentioned, it is a core property of the Reals that there are uncountably many of them, and it is not possible to create a set with aleph-1 cardinality by pairing up a finite number of elements picked from an aleph-0 set. So how then can we construct a Real number? Let’s discuss three popular approaches.

The Axiomatic Approach

The easiest way to create a new mathematical object is to simply assert its existence. We don’t have to construct the Real numbers through a set of ingenious logical steps if we can just axiomatically define them. Recall the mention of the Peano Axioms in the section on Natural numbers that served as a starting point for our construction of the Naturals, the Integers and the Rationals. We always need axioms, but I think it’s fair to demand that any mathematical theory which aims to get taken seriously must try to restrict itself to the minimum number and the simplest kinds. The axiomatic approach to the Real numbers can be—flippantly—summarised as follows:

- The Real numbers totally exist, bro.

- All arithmetical operations just work.

- Trust me, bro.

In actuality, what this approach states is that every Real number is an infinite decimal expansion where each decimal can be whatever it wants to be. I.e. there need not exist a pattern or algorithm which constrains the digits in any way. This requires a weak Axiom Of Choice, which states that it is possible to individually select an infinite amount of values, even if a distinct choice must be made each time. In the case of a Real number, we must pick one of the digits from 0 to 9 for each of the countably many decimal positions. So we could for example create a Real number by starting in the following way:

0.3857126408236476254081436248…

This is of course woefully incomplete. It is not possible in this universe to specify an infinite amount of information. The number of particles and the number of Planck volumes we have access to is large, but nowhere near infinite. Every Real number written down using this cut-off notation is really just a Rational number using a set of ellipses to pretend it’s more than it is. But let’s not be boring and reject something just because it cannot be done in the real world. Let’s instead ask how we might perform arithmetic on axiomatic Reals. I want you to imagine I have two honest-to-goodness Real numbers written in my notebook and I will give them to you one decimal digit at a time. Your job will be to compute the sum of these two. The first is already written above, and the second one starts like this:

0.2142873591763523745918563751…

If your answer has more accuracy than 0. you’ve made a mistake. Well, maybe. We cannot add 0.3 to 0.2 for a sum total of 0.5 because it’s possible we may end up with a carry, so the 5 in the tenths decimal place is a decent guess, but it may turn out to be a 6. To find out which, we have to add the hundredths digits 8 and 1 for a total of 9. But we can’t be sure about the 9, as there may be a carry involved. In fact each of the subsequent pairs of digits that you can see add up to 9 meaning you won’t be able to decisively choose between an initial 5 or 6 until you come across a definite overflow with carry, or definite underflow without. And I’m allowed to keep picking pathological digits like this for as long as I wish as per the Axiom Of Choice. I won’t even suggest you try and multiply two Real numbers written in this way. It is practically impossible, which is why we need to axiomatically declare arithmetic to be possible.

The Dedekind Cut

Richard Dedekind was one of the major proponents of the—then—newly invented Real numbers and I assume he was not much happier with the axiomatic construction than I, which is presumably why he created a new construction, named in his honour. At first glance it’s a pretty good idea, predicated on the notion that an irrational number like the square-root of two splits the set of all rational numbers into two disjoint subsets. One subset containing all those fractions which are less than root-2, and another subset containing all the other rationals. So why not define a Real number to be the upper limit of the set of all rationals less than it? We can write a Dedekind cut using set notation, which initially seems like a major improvement over an infinite avalanche of axiomatic decimals, but it quickly becomes apparent it suffers from its own drawbacks.

First of all there’s a reason why every single example of a Dedekind cut you will ever see is for the square root of 2. Trying to write a set builder to define the Dedekind cut for numbers like pi, e, sin(87°) requires a masters degree and a long weekend. There is the additional—and much more severe—problem that set builder notation must consist of a finite number of symbols picked from a finite alphabet. As already mentioned earlier, that is insufficient to define an uncountable number of distinct sets. At best, Dedekind cuts are a construction for some set-based field of computable numbers, whose cardinality is equal to that of the Naturals.

Cauchy Sequence Equivalence Classes

The last construction of the Reals I will discuss is one based on numeric sequences. It is, again, a lovely idea at first glance and I particularly like it because unlike the previous two attempts it really drives home the excessive infiniteness of the Reals. The starting point here is the observation that some rational number sequences (particularly never-ending ones) tend to get closer and closer to some limit value. More specifically, a sequence can be considered Cauchy when for any small but positive rational accuracy, it is possible to pick an index within the sequence beyond which it never strays further than that. Then, by picking successively tighter and tighter accuracies, we can approach the limit of the sequence in a very controlled way.

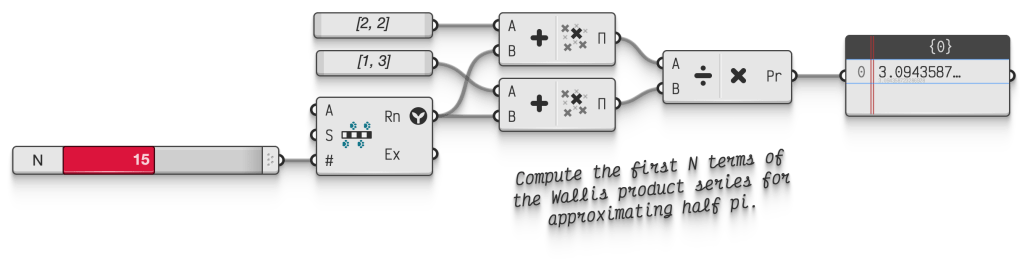

For example, here are the first few terms of the Wallis Product sequence, which is a charming albeit very inefficient way to approximate pi:

2.666…, 2.844…, 2.9257…, 2.9722…, 3.0022…, 3.0232…, 3.0387…, 3.0506…, 3.0600…, 3.0677…, 3.0741…, 3.0794…, 3.0839…, 3.0879…, 3.0913…, 3.0944…

Pi is an irrational number, and all the values in Wallis’ sequence are rational, so at no point does pi occur in this sequence. Yet, if we travel far enough, we can reduce the error between the sequence and the ‘real’ pi to as small a non-zero accuracy as we’d like. It is therefore a perfectly sensible idea to assume that pi in fact is the limit of the Wallis sequence.

But there are many other famous sequences which also approximate pi, and in this same sense therefore must be pi. So the construction of pi must include all of these sequences, hence the “equivalence class” portion of the construction. So in this scheme, a Real number is constructed by collecting all the Cauchy sequences which share the same limit.

Note it’s not just famous sequences which are part of this construction, but all possible sequences. And given any Cauchy compliant sequence, we can create an infinitude of other sequences, all Cauchy compliant as well. We can change the first number in the original sequence to any other value, and the remainder of the sequence will still behave like a limiting sequence. Or we can change the second number to any value we please. Or the third. Or the first and the second. We can modify any finite amount of the leading terms of any Cauchy sequence to whatever numbers we like. This has the unfortunate outcome that any finite approximation of a Real number looks like every other Real number when constructed via Cauchy Sequence Equivalence Classes, because they all share all possible sequences which start with all possible numbers.

So what now?

Where does this leave us?

Exactly where we were before you read this. I am not a mathematician and you shouldn’t be listening to me about this. None of these arguments are original, I have merely heard them expressed by real mathematicians and have become convinced by them. I’ve looked fairly hard for counter-arguments and rebuttals but have found none, which could either mean these ideas are so fringe that nobody bothers refuting them, or possibly that nobody has good counter-arguments, or possible something in between.

Without the Real numbers, the continuum crumbles and along with it a lot of mathematical work done over the past two centuries. I do not know if something is truly broken. And if it is I do not know where to begin fixing it. I hold these unpopular opinions merely until someone disabuses me of them.

As a parting gift I should like to recommend the best book I have read in my attempts to solidify my views on this topic: The Real Numbers: An Introduction to Set Theory and Analysis by John Stillwell.

It’s a very well written book clearly aimed at mathematicians but digestible by a wider audience. Sadly it did not dive too deeply into the construction of the Reals, but it was nevertheless a lovely read filled with gorgeous set-theoretical arguments as to why some things simply must be true. I fully admit to not making it past superfilters.

- Technically Naturals and Integers are rings, while Rationals and Reals are fields. I’ve chosen to not use these terms and refer to all of them as systems instead, which is not official nomenclature. ↩︎

- Whether one includes zero in the naturals is a personal choice, though in modern times it usually is. I think the naturals are more parsimonious without zero. ↩︎

- There are infinite ways of writing integers this way, as [7,1] is equal to [8,2], and equal to [9,3] and so on. This plurality is called an equivalence class. ↩︎

- Sadly exponentiation is broken in the integers, as there is no way to raise integers to negative powers and end up with other integers. ↩︎

Leave a comment